Another UK General Election has come and gone, with winners and losers amongst the survey firms as well as the politicians. Once again most people seem to be stunned by the result; while the adjustments made after the last election look like the key reason they didn't get this one broadly right. Who'd be a pollster? Less than 24 hours after the results started to come in, you can if you wish already read a vast amount about what worked and what didn't, and critiques ranging from scholarly to poll-bashing - so we make no apology for quoting others liberally in our six-point summary.

Less than 24 hours after the results started to come in, you can if you wish already read a vast amount about what worked and what didn't, and critiques ranging from scholarly to poll-bashing - so we make no apology for quoting others liberally in our six-point summary.

1. There were a very broad range of final predictions. Some of them were bound to be wrong, even before we saw any results! In the event, the margin of 2.4% between the parties was at the low end of what pollsters said, but within the range. See Wikipedia.

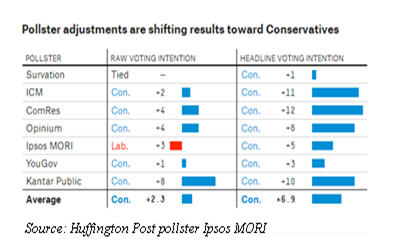

2. Adjustments made to the initial polling data following the BPC / MRS inquiry into the 2015 errors actually pushed most of the companies in the wrong direction (see chart, courtesy of Ipsos MORI in the Huffington Post) - they would have been relatively accurate if they had not factored in 'Shy tories' and the tendency of young voters to stay at home, as Peter Kellner points out in an article for the Evening Standard. Arguably Kellner's title is rather harsh (General Election polls 2017: How the pollsters got it wrong) given that the article goes on to point out that a number of companies got things broadly correct:

With one exception the polls tried too hard. Their raw figures generally pointed to a bad night for Theresa May. Had they stuck with these numbers, they would have redeemed their reputation.

Instead, burnt by their failure to predict David Cameron's victory two years ago, they adjusted their data in the belief that many young Labour supporters would end up staying at home.

So to borrow our phrasing from the U.S. election, when we said that Donald Trump was only a 'normal-sized polling error' away from winning the Electoral College, May's Conservatives are now only a normal-sized polling error away from a hung parliament. On average in the UK, the final polling average has missed the actual Conservative-Labour margin by about 4 percentage points. (This is twice the average error in US presidential elections.) If Labour outperforms its polls by that margin, Conservatives would win the popular vote by only about 3 points - and May would probably have to find a coalition partner to form the next government. If the polls were to miss by any more than that in Labour's favor, a variety of yet-more-unpleasant scenarios could crop up for May, including some where Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn tried to form a government instead.

...These experiences have given rise to what I've called the First Rule of Polling Errors, which is that polls almost always miss in the opposite direction of what pundits expect.

It seems that whether people voted Leave or Remain in 2016's European referendum played a significant part in whether they voted Conservative or Labour this time. Did the 2017 campaign polls factor this sufficiently into the modelling of their data?

If younger voters came out in bigger numbers, were the polls equipped to capture this, when all experience for many years has shown this age group recording the lowest turnout? (DRNO Editor: see some good analysis by Kantar of the age factor).

Also, the variations in voting across Britain at this election appear much more complex than in previous elections and that poses real challenges to polls seeking to reflect the national picture. We have seen great movements in Scotland; Labour taking Canterbury and Enfield Southgate but losing a core seat such as Mansfield and sustaining a big swing in Bolsover.

The future seems very challenging for the pollsters.

It is important for all of us that the pollsters succeed. If their reputation collapses then a space is created that will be filled by any number of spinners and fraudsters. Politics, like nature, abhors a vacuum and if polls are discredited then any number of people will step in to give their partial and partisan interpretation of events. National samples will be elbowed aside by the wisdom of tweets and Facebook friends.

I hesitate to call for inquiries - after all, we had one post-2015. But I think post-2017 we have to allow more time for proper scrutiny of the various methodologies. In 2015 there was great pressure for a quick answer: 2017 suggests there is no such thing.

All articles 2006-23 written and edited by Mel Crowther and/or Nick Thomas, 2024- by Nick Thomas, unless otherwise stated.

Register (free) for Daily Research News

REGISTER FOR NEWS EMAILS

To receive (free) news headlines by email, please register online